If Soho’s adult bookshops of the 1960s and ’70s were part of a hidden economy, then men like Joey Janes were its frontline staff—visible, vulnerable, and disposable.

Janes’ 1974 police statement—given to detectives from the Metropolitan Police’s A10 unit during their investigation into corruption within the Obscene Publications Squad—offers a glimpse into how that economy functioned. His testimony, while not always reliable, remains a valuable account of the bookshop chair system: a method by which true owners shielded themselves from legal consequences by installing leaseholders to front their operations.

In Janes’s case, he worked at The Court Bookshop, 10 Walkers Court; one of the largest adult shops in Soho, owned by Tony Sonenscher. On paper, Janes leased the shop. In reality, Sonenscher controlled the business—taking the takings, paying the bills, sourcing the stock, and, crucially, paying off the Obscene Publications Squad for what insiders knew as the corrupt ‘licence’ to do business. This informal system of protection allowed select porn shops to operate largely undisturbed while others were repeatedly raided and closed down.

10 Walker’s Court had started life as the Kenny Lynch Record Centre, previously leased by the eponymous Black British entertainer. But when the business failed, Sonenscher and Janes transformed the site into a porn shop; Janes claims that this was his idea. Sonenscher was new to the trade and unsure at first. “Can we do that?” he asked. “No problem,” Janes replied. “We’ll sell all the material and crack away.” And so they did.

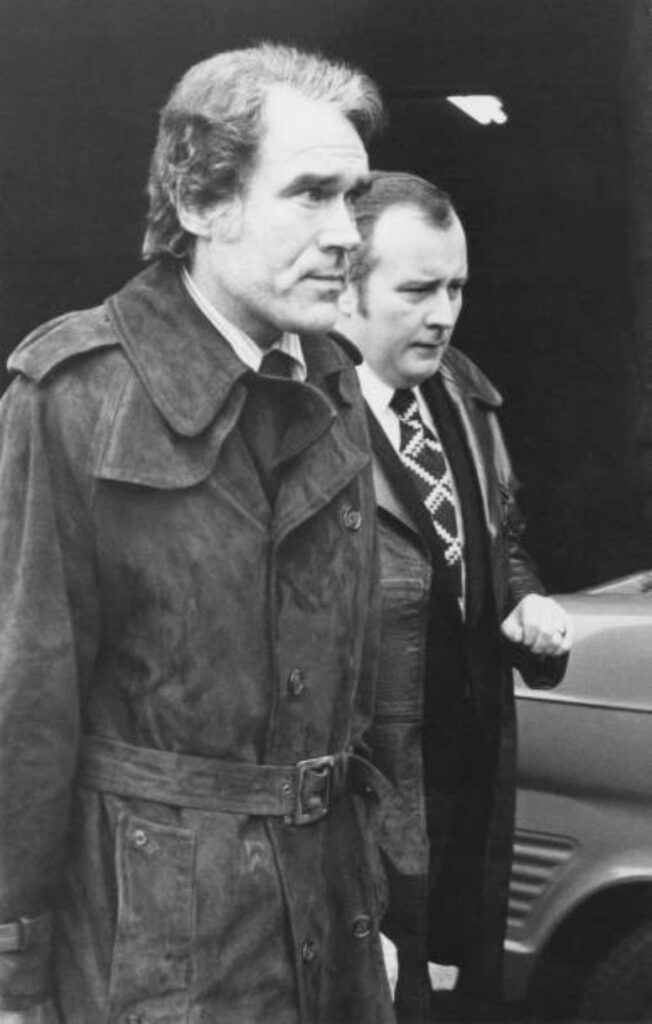

Once figures like Brian Young entered the picture—brokering connections with the police—the business began to boom. But it was Janes, not Sonenscher, who took the risk. He was twice raided by the porn squad and charged, while Billy Hicks—one of Sonenscher’s relatives—was simply allowed to walk out. “The police didn’t even attempt to question Billy,” Janes recalled. “They walked straight into the back room.” It was there, in a specially constructed area behind the counter, that the more explicit material was sold.

Janes earned a modest wage—£50 a week at one point—and described himself as “only here to get a living.” But he was deeply embedded in Soho’s broader sexual economy. From the early 1960s, he worked in drinking clubs, clip joints, and nude posing establishments, before moving into bookshops. He had spells working for the so-called ‘Godfather of Soho’ Bernie Silver (famously linked to the Messina brothers and other organised crime figures) and Jimmy Humphries (one of Soho’s most prolific and protected pornographers). His CV included addresses across Soho, including Berwick Street, Frith Street, Rupert Street and Old Compton Street.

One of the more extraordinary moments in his statement comes when Janes describes Sonenscher’s brother-in-law, Frank, doing home renovations for the very police officers charged with enforcing the law. Frank, he said, tiled the kitchen of none other than DCS Bill Moody—the corrupt head of the Obscene Publications Squad. Such acts of domestic favour weren’t uncommon; they were part of the soft, everyday mechanics of Soho’s protection economy.

Despite regular clashes with Sonenscher over pay, control, and recognition, Janes kept going back. “It was all aggravation,” he said. “But I was quite happy here. I was peaceful.” The relationship was fraught but persistent—a mixture of dependency and exploitation that kept many chairs tied to their benefactors.

What Janes’s statement makes clear is just how central the chair was to the running of Soho’s porn trade. These weren’t minor employees—they were the legal face of the business. They signed the leases, registered the companies, appeared in court, and faced imprisonment if things went wrong. In return, they were offered modest pay, legal support, and the illusion of agency. But the real control—and the profits—remained with the men in the background: operators like Sonenscher, Humphries, or John Mason, who structured their empires on the plausible deniability the chair system offered.

Janes may not have made much money, but his story helps reveal how the system really worked: part criminal enterprise, part bureaucratic sleight of hand, entirely dependent on a network of willing fronts.